This article first appeared in the July/August 2012 issue of American Spirit. You can subscribe to the magazine at DAR.org.

Note: One of the wonderful things about working with clients like the Marine Corps League and the Daughters of the American Revolution is how we are reminded throughout the year — and not just on holidays like the Fourth of July — of just how much those who came before us sacrificed to preserve the liberties and freedoms we too often take for granted.

To celebrate Independence Day, we are posting a patriotic article that appeared in the July/August 2012 issue of American Spirit, the magazine of the DAR. As anyone, not just DAR members, can subscribe to the magazine, we wanted to share an example of its great content and encourage you to subscribe.

In the article, Hammock senior editor Bill Hudgins takes a closer look at some of the symbols of America, like the Great Seal and the bald eagle, that were deliberately chosen, as well as others whose origins are wrapped in folklore.

Around the world, if you showed anyone a picture of Uncle Sam, the U.S. flag or the White House, they’d almost invariably associate it with America and Americans. Many others would also recognize the Great Seal of the United States, the Liberty Bell and the bald eagle.

But pictures of a rattlesnake chopped into eight parts or coiled to strike would probably draw a baffled look outside our borders. And how many people anywhere would recognize drawings of “Brother Jonathan” or “Columbia” as emblematic of the United States of America?

Yet all of these have at some time reigned as widely known symbols of our nation. Some, like the Great Seal, were deliberately created, while the origins of others are wrapped in tradition, legend and folklore.

As our nation celebrates its 237th birthday, American Spirit presents some of our most well-known and iconic symbols and their often quirky histories.

Yankee Doodle, Brother Jonathan and Uncle Sam

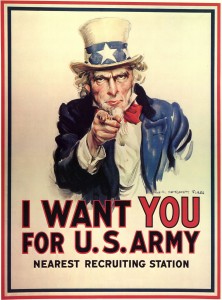

Uncle Sam recruitment poster

via Wikipedia Commons.

Like a character from Dickens, “Yankee Doodle” had a tough beginning but rose to greatness along with America.

Yankee Doodle was originally a mildly derisive British term for the colonists: “Doodle” was slang for a silly person or bumpkin; the origins of “Yankee” are not clear.

As a song, “Yankee Doodle” was popular long before the Revolution. The original American lyrics are credited to a British military surgeon, Dr. Richard Schackburg. According to tradition, he wrote the words in 1755 while attending a wounded prisoner of the French and Indian War quartered at Fort Crailo in Rensselaer, N.Y. (Also known as Yankee Doodle House or Crailo State Historic Site, the house lent its name to the Fort Crailo DAR Chapter, which was actively involved in getting it listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1962.) The tune’s origins are far murkier, ranging from Great Britain to Eastern Europe.

Reportedly, British troops sang or played the song while marching to reinforce units at Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. But when the smoke cleared, it was the victorious colonists who sang the song at the backs of the retreating Redcoats—and again some years later when the British surrendered at Yorktown.

“Brother Jonathan” was another early personification of Americans, often in contrast to England’s “John Bull.” His origins are unclear, though the most common explanation is that George Washington used it as a nickname for Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull. In meetings, Washington often reportedly said, “Let us hear what Brother Jonathan has to say about this.”

Later, the image of Brother Jonathan evolved into a man in his prime, brawny and stalwart. His name was attached to everything from a newspaper to a steamship. An 1827 book called The Diverting History of John Bull and Brother Jonathan by American author James Kirke Paulding was a satirical allegory on the rocky relations between the United States and Great Britain. And on March 25, 1861, Oliver Wendell Holmes penned “Brother Jonathan’s Lament for Sister Caroline,” which grieved for South Carolina and the imminent catastrophe of the Civil War.

In the Civil War, Brother Jonathan symbolized the Union. He was sometimes depicted as wearing striped trousers, a top hat, a long-tailed coat and a star-spangled shirt, imagery that would soon transfer to his successor, Uncle Sam.

Uncle Sam’s origins are popularly traced to Samuel Wilson, of Troy, N.Y., where he was widely known as “Uncle Sam.” He and his brother, Ebenezer, won a contract to supply meat to the Army during the War of 1812. The barrels of meat were stamped “U.S.,” meaning they were government-issue, but New York residents and soldiers who knew him quickly redefined it to mean “Uncle Sam.” [Later: See Update.]

As Brother Jonathan receded from the public mind during and after the Civil War, Uncle Sam assumed many of his characteristics, while aging and growing a beard. Today, the most famous depiction of Uncle Sam is the World War I-era.

“I Want You” recruiting poster created by James Montgomery Flagg. That stern, craggy visage clad in red, white and blue has become the benchmark for all other variations.

Columbia

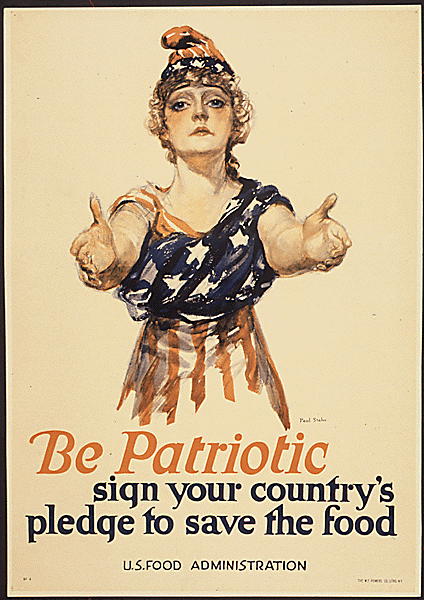

Paul Stahr illustration of Columbia for “Be Patriotic” poster, circa 1917-18, via: Wikipedia Commons.

Like Brother Jonathan, the figure of Columbia as representative of America has faded from public awareness; today, she is probably most often associated with the logo of the Columbia Pictures movie studio.

Yet, Columbia’s name is everywhere, from the District of Columbia to dozens of counties, towns and natural features such as rivers, creeks and mountains.

A Latinized version of Christopher Columbus’ name, Columbia means “Land of Columbus.” Envisioned as a woman since at least the early days of the Revolution, Columbia’s parentage is obscure. In 1697, Chief Justice Samuel Sewall of the Massachusetts Bay Colony wrote a poem proposing the feminine name Columbina for the Colonies as a whole. As a reference to America, Columbia appeared as early as 1738 in a British newspaper’s report on Parliamentary debates as a euphemism for the American Colonies. By the Revolution, Columbia was firmly associated with America as a kind of guiding spirit. In 1775, former slave and poet Phyllis Wheatley invoked Columbia in her poem “To His Excellency General Washington,” following his appointment as head of the Continental Army:

Celestial choir! enthrond in realms of light,

Columbia’s scenes of glorious toils I write.

While freedom’s cause her anxious breast alarms,

She flashes dreadful in refulgent arms.

Throughout the 19th century and early 20th century, Columbia reigned as queen of female symbols for America until she was eclipsed by the Statue of Liberty. She was often portrayed wearing an American flag and a soft cap of some kind. “Hail Columbia” was the unofficial national anthem until the selection of “The Star-Spangled Banner” in 1931. “Hail Columbia” is now the vice president’s official entrance music.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/82867806″ params=”” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

The Bald Eagle and Great Seal

Great Seal of the United States via Wikipedia Commons.

After years of debate, in 1782 Congress finally adopted the bald eagle as America’s national bird and also settled on a design for the Great Seal of the United States. Believed to be unique to the United States, the eagle deserved to be our national bird, Congress thought, because it symbolized strength, courage, majesty and freedom.

Benjamin Franklin, however, famously derided the eagle as a symbol, at least as it was depicted on the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati. In a letter to his daughter Sally, he wrote:

“I wish that the bald eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country, he is a bird of bad moral character, he does not get his living honestly, you may have seen him perched on some dead tree, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the labor of the fishing-hawk, and when that diligent bird has at length taken a fish, and is bearing it to its nest for the support of his mate and young ones, the bald eagle pursues him and takes it from him … Besides he is a rank coward; the little kingbird, not bigger than a sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the district. He is therefore by no means a proper emblem for the brave and honest … of America … For a truth, the turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird, and withal a true original native of America … a bird of courage, and would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British guards, who should presume to invade his farmyard with a red coat on.”

Sadly, both the eagle and the wild turkey came close to extinction in the next two centuries, due to destruction of habitat and overhunting—farmers shot eagles whenever they could to prevent them from preying on young animals. Eagles again became endangered in the mid-20th century before being declared a protected species.

While every member of Congress knew what an eagle looked like, the nation’s Great Seal was an abstraction. Congress adopted the seal on June 20, 1782, without ever seeing an actual drawing of the design. What Congress approved was a highly detailed description and explanation of the two-sided seal drafted by Charles Thomson, the Secretary of Congress, whose design included elements from several previously rejected designs.

A nation’s seal represents that country’s core beliefs, virtues and values through symbols and imagery. The Secretary of State is the official custodian of the Great Seal. According to a Department of State publication “The Great Seal of the United States,” Thomson told Congress:

The red and white stripes of the shield “represent the several states … supporting a [blue] Chief which unites the whole and represents Congress.” The colors are adopted from the American flag: “White signifies purity and innocence, Red, hardiness & valour, and Blue, the colour of the Chief, signifies vigilance, perseverance & justice.” The shield, or escutcheon, is “born on the breast of an American Eagle without any other supporters to denote that the United States of America ought to rely on their own Virtue.” The number 13, denoting the 13 original states, is represented in the bundle of arrows, the stripes of the shield, and the stars of the constellation. The olive branch and the arrows “denote the power of peace & war.” The constellation of stars symbolizes a new nation taking its place among other sovereign states. The motto E Pluribus Unum, emblazoned across the scroll and clenched in the eagle’s beak, “expresses the union of the 13 States.”

There have been seven official seals made since 1782, and none has fully translated Thomson’s description into perfect physical reality. Each seal has varied from the approved description. Engravers interpreted or visualized elements in different ways and introduced errors or innovations that later craftsmen copied and perpetuated.

In 1885 Secretary of State Frederick Frelinghuysen commissioned Tiffany & Co. to execute a new seal faithful to the original description. This design was notable for giving what had been a rather spindly eagle a much more powerful, muscular appearance.

In 1986, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing made a master die for the seal, which was the template for the seal that is actually used on some 3,000 documents a year. Barring redesign, this master template will be the standard for the future.

The National Flag

The original Star-Spangled Banner, via the Smithsonian.

As with many symbols, the precise origins of our national flag are a blend of fact and tradition. On June 14, 1777, the Continental Congress passed the original Flag Act: “Resolved, That the flag of the United States be made of thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation.”

These vague instructions led to a number of variations, with stars arrayed in rows or circles and having different numbers of points. Elizabeth “Betsy” Ross was only one of several prolific flag makers who interpreted these instructions. Others included Cornelia Bridges and Rebecca Young of Pennsylvania, and John Shaw of Annapolis, Md. The design known as the Betsy Ross flag, with 13 stars in a circle on a blue field, was in use until Vermont and Kentucky joined the union in the mid-1790s.

By the War of 1812, the U.S. flag had 15 stars and 15 stripes. This was the flag that was raised over Fort McHenry near Baltimore on September 14, 1814, after British bombs and rockets rained down through the night. In the “dawn’s early light,” Francis Scott Key could see the U.S. flag still flew and that the British were withdrawing.

The original Star-Spangled Banner, measuring 30 by 42 feet, was sewn by Mary Pickersgill (1776–1857) with the assistance of her 13-year-old daughter Caroline; teenage nieces Eliza Young and Margaret Young; and Grace Wisher, a 13-year-old African-American apprentice.

Within a few years, the flag acquired another nickname, this one attributed to shipmaster William Driver of Salem, Mass. As he was about to set sail in 1831 for the Pacific, he was given a handmade flag for his ship, the brig Charles Doggett. As the flag was run up and caught the breeze, it unfurled smartly, prompting Driver reportedly to exclaim “Old Glory!”

When Driver retired in 1837, he moved to Nashville, Tenn., taking “Old Glory” with him. When Tennessee seceded from the Union, Rebel soldiers who knew of the flag tried repeatedly and unsuccessfully to find it. Old Glory came out of hiding after Union forces captured Nashville, when it was removed from its hiding place—it had been sewn inside a quilt—and flown over the state capitol building.

The Statue of Liberty

Statue of Liberty, photo by Sue Waters, via Flickr.com, Creative Commons.

No other monument so exemplifies America today as the Statue of Liberty. Her far-seeing gaze has welcomed millions of immigrants and travelers to the Land of Liberty since 1886.

The statue was designed by Frédéric Bartholdi as a gift to the United States from her Revolutionary War ally, France. She represents Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom; her tablet, which symbolizes the rule of law, is inscribed with July 4, 1776.

Bartholdi completed the head and torch-holding arm first, and these were shipped to America to fire enthusiasm and raise funds for the pedestal. The arm was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition and then stood in Madison Square Park from 1876 to 1882.

The remaining pieces of the statue were shipped to New York in 1885 aboard the French ship Isere, which nearly sank in rough seas before it arrived on June 17, 1885.

However, the statue’s pedestal on Bedloe’s Island had not been completed when the shipment arrived, so the crates had to be stored. Fundraising had gone slowly, prompting New York World publisher Joseph Pulitzer to launch a massive campaign in his newspaper. The campaign succeeded: Some 120,000 individuals contributed, many of them chipping in less than $1. The pedestal was completed, the pieces assembled and she was dedicated on October 28, 1886.

Update: (July 4, 2013) According to new (or, in this case, old) information from superstar lexographer Ben Zimmer (of the Wall Street Journal, Vocabulary.com, etc.), the Samuel Wilson founding myth has been up-ended by prior mythology. According to Log Lines, the blog of the USS Constitution Museum in Charlestown, Mass., “Uncle Sam” as a stand-in for the U.S. government is cited in a March 24, 1810 journal entry by Isaac Mayo, then a Navy midshipman. Here is the museum’s transcript: “weighed anchor stood down the harbour, passed Sandy Hook, where there are two light-houses, and put to sea, first and second day out most deadly seasick, oh could I have got on shore in the hight [sic] of it, I swear that uncle Sam, as they call him, would certainly forever have lost the services of at least one sailor.”